This post is part of a year-long series. If my work is helpful for you, consider a contribution through Venmo to support this crucial work of unlearning racial bias.

At the end of piece five, I left you with a list of questions to guide you in some self-reflection. One reason I was able to come up with the questions quickly is that I’ve been on the receiving end of several of them. I’ve been shushed by a white friend in a restaurant for wanting to send back food that had hair in it. I’ve been confronted by the principal of the campus I worked on and told I was brittle and standoffish for not smiling in the hallways, for not always responding “hello” when greeted [even though in all likelihood the loud, crowded hallways prevented me from hearing his greeting to begin with]. I’ve had my campus principal called by a workshop host because in my frustration, I asked questions, and then, when it seemed I was asking too many so I shifted my focus to note-taking, the workshop presenter found my smile odd – apparently – when she came to ask how I was doing.

I’ve been labeled intimidating because I am confident, introspective [read: quiet when thinking/regrouping], and opinionated. While this may seem harmless, when people feel intimidated, they tend to do whatever they can to knock down the people who intimidate them. In some ways, to me, “intimidating” is the new “uppity.”

But alas, this week, we’ll shift our focus away from the violence of stifling black people’s autonomy, toward a different kind of violence: the kind that invades a sacred space.

Churches in this country are segregated not only by race but also by culture, ideology, theology, and politics. While white supremacist racism was the reason for the black church’s emergence separate from white churches in this country, it is not the only reason the black church has remained. Black churches are our haven. Here, we find catharsis, community, engagement, help, peace, family, acceptance, and connection. From the time we are pre-schoolers, we learn Easter speeches, watch our older cousins perform praise dances and mimes, pass out on our grandmothers’ laps during the sermon, and sneak more peppermints from our mothers’ purses than they realize. In black churches, we exhale – away from staring eyes that wonder aloud about our hair texture, cultural references, or blaccents. We are free to live and move and have our being without explaining how we exist the way we do in this world.

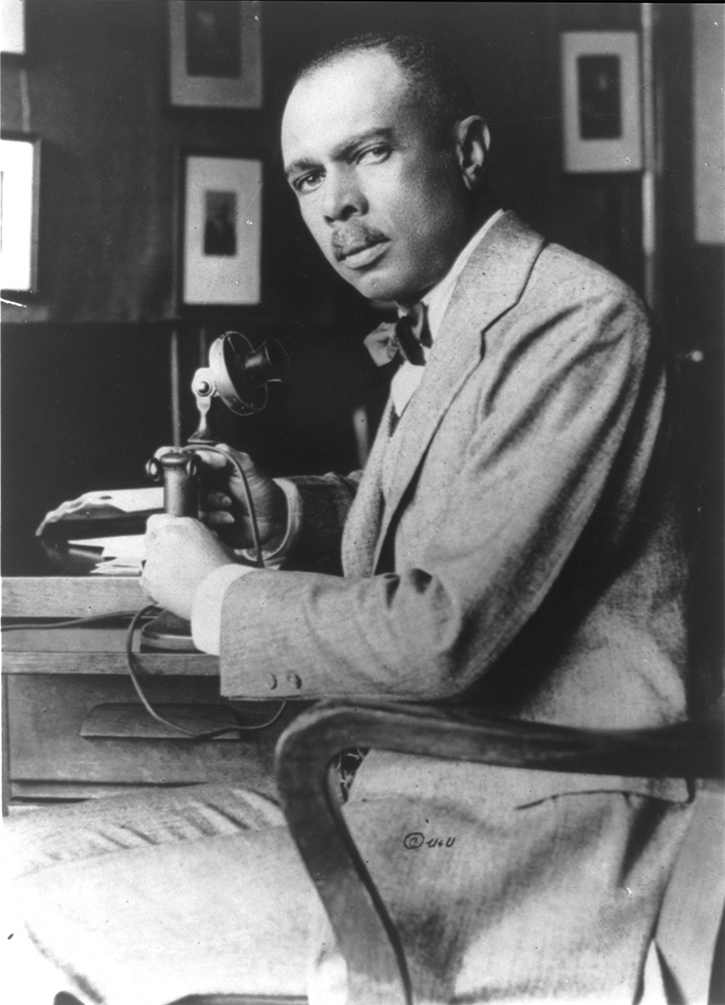

author of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,”

Courtesy: Library of Congress

And we sing.

At least once a year – in my experience – we sing the black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” My church back home would switch out the congregational hymn at the beginning of each month. For every February I can remember, this anthem was that month’s congregational hymn. Today, even without a hymnal to guide me, I can sing most of the words by heart. The familiar tune carries in it a feeling of home for me, a sense of connectedness that is deeper than I have words to express.

Last week, an anonymous person who claims to be in discussion regarding racial tension in the NFL claimed that “Lift Every Voice and Sing” will be played before “The Star-Spangled Banner” for week one games in September.

This is a terrible idea for a plethora of reasons. If the NFL follows through with this supposed plan, I fear that the opening anthem sequence will lead black and white sports fans to sit, stand, kneel, seethe, and likely argue and eventually swing at each other as much as they physically can before the songs end.

Permeating all the tension is a violent act visited upon a space black Americans hold as sacred. Out from the gloomy past of our people being forced to create their own churches, traditions, and culture, have emerged a richness we hold dear. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is not a call to conflate cross and country as we tearfully revere America’s founding fathers. Instead, the black national anthem is a holy call to remember our people’s oppression, faith, struggle, triumph, and resilience.

Simply put, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” belongs to those of us whose weary years and silent tears have been seen by God. It is a hymn of worship to God, not an anthem of allegiance to a flag.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” is at best a patriotic call to take off one’s hat and fall silent while thinking of people who have died for freedoms all citizens can enjoy. At worst, Francis Scott Key’s anthem is a tone-deaf call to remember American whiteness fondly while overlooking the writer’s own view of black people as subservient, subhuman. So for the same national sports organization that blackballed Kaepernick for kneeling in memory of citizens victimized by police brutality, to now invite itself into a sacred space black Americans have made for ourselves, is at best naive and ill-fitting – and at worst, violent and blasphemous.

This week’s suggested resources will hopefully help illuminate the meaning of the black national anthem to our community. First, I suggest a close reading of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” I encourage you to read each verse and reflect on its meaning, depth, and the collective history it incorporates. Second, I suggest taking a look at Beyoncé’s “Homecoming” on Netflix. She began her show with the black national anthem, and the spectacular concert that followed carried an HBCU theme, which I think will help to further highlight the beautiful, affirming traditions and institutions black Americans have created for ourselves, after being banned from white American spaces that never intended to include us except as servants. Third, I hope you’ll take a careful look at the lyrics to all three verses of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The anthem, like our country, has a complex author with a complicated and at times conflicting history.

Some questions to consider as you read and watch this week:

- When you first heard of Colin Kaepernick’s protest during the national anthem, what was your reaction? Why?

- When and where, in your opinion, are the right time and place to protest injustice?

- Think of your family’s favorite song, tradition, or hymn. If your family member was publicly harangued by a group that later wanted to play that hymn publicly, but still had not repaired its broken relationship with your family member, how would your family feel?

I hope you’ll sit with these texts and these questions this week. Get quiet and determine what these songs and traditions mean to you, how important they are in your life. I’ll see you here again next week so we can keep working toward peace, one piece at a time.

❤