This post is part of a year-long series. If my work is helpful for you, consider a contribution through Venmo to support this crucial work of unlearning racial bias.

The title song of the playlist I created last week was “Hell You Talmbout.” In this protest anthem, the singers alternate a chanted refrain of the title and shouted verses with the names of a small fraction of black people who have been killed as a result of living within this society. A society which in too many ways regards blackness itself as suspicious, as reason enough to shoot first and ask questions later. Among the names of those victims mentioned in the song, I was unfamiliar with four: 16 year-old Kimani Gray, young mother Miriam Carey, veteran Tommy Yancy, and Guinean immigrant Amadou Diallo.

May light perpetual shine on each of their souls.

I asked at the end of that post why the recent murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery unsettled you in a way prior murders did not. My own answer to this question is that I am angrier and more heartbroken now, but this isn’t my first time feeling tired and angry. I asked, too, why you’re ready for this conversation now when you weren’t before. My answer is that I’ve been ready in small, interpersonal ways, but I’m ready to write this series now because my kids are old enough that my fear for their safety is incredibly real, and because I want newly aware, well-intentioned white people, to stop listening exclusively to their white friends who are just now talking about race.

Listen to, read, watch, and follow black activists and organizations who are already engaged in this work. They have been living this reality for a long, long time.

During our country’s current emotional upheaval and broad push for justice in the name of murdered citizens, for substantial police reform, and for urgently needed policy change, I’ve begun to notice the spectre of a decades-old argument. Specifically, when actors Nicholas Ashe and Justice Smith announced their relationship and joined a recent protest, some of the public comments responding to their announcement called for them to set aside their sexuality because now is the time to focus on blackness.

It seems that in these commenters’ minds, Ashe and Smith are welcomed to be a part of this movement for black lives if – and only if – they set aside their relationship and identity as queer men so as not to “distract” from the protests or cause people to “lose focus” or “take attention away from the issue at hand.” In addition to the fact that this argument overlooks the queer, intersectional foundations of the movement, it also implies that these activists’ queerness otherizes them and somehow waters down their blackness and therefore the push for justice itself.

This is wrong. And it is also not new.

I confess that I’ve had to reflect on this recently. I consider myself an affirming Christian, yet there came a moment when I sat across from a friend who shared a personal truth, and I had to question my inner reaction. In my zeal to loudly affirm and learn from my LGBTQ friends, I hadn’t stopped to consider that there’s more than one valid way to exist within that spectrum. And my loud affirmation could easily be read as condemnation for folks who don’t live out their LGBTQ identity in the way I think they should. That was wrong of me.

I have three books to suggest to you this week – all of which I have listened to as audiobooks in the past few years. Because each book contains heavy, emotional, deeply personal content, I’ll provide a synopsis of each. My suggestion is you choose the one you think you will allow you to be open and able to understand most easily.

Gay Girl, Good God is phenomenal speaker Jackie Hill Perry’s frank account of her journey from self-identifying as a lesbian, to her struggle with addiction, to her encounter with God and conversion to Christianity, which ultimately led her to embracing a wholly different lifestyle than what she led before. (To be transparent, I struggled with the epilogue of this book and its language of “disordered sexuality.” Therefore, I did not finish it.)

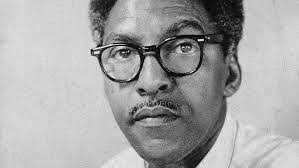

Bayard Rustin, the openly gay activist who was instrumental in organizing 1963’s March on Washington – the march where Dr. King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, the march that Al Sharpton has announced plans to replicate this August – was in many ways kept behind the scenes of the Civil Rights Movement because of his status as an openly gay man. Then, as now, folks thought that his sexuality would be a distraction if he featured more prominently in the movement.

In When They Call You A Terrorist, Patrisse Khan-Cullors details her early life, her involvement as a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter Movement, her experience being harangued as a terrorist, and shares with readers the unconventional way she came to fall in love, marry, and have a child with her partner.

Janet Mock’s Redefining Realness is a searing, heartbreaking account of her childhood as her parents’ first son. She chronicles her unique upbringing in a culture whose roots regarded transgender people as rare and worthy of reverence, and she recounts an experience many transgender youth face – resorting to extreme and dangerous measures to bankroll the medical treatment and procedures she desperately desired.

I have several reflection questions for you this week. They are designed not to elicit a certain right or wrong answer, but to prompt you to question your own biases:

- What qualifiers are you placing on black people whose lives you think are worthy of saving/protecting?

- In your mind, do you expect that if black activists are members of the LGBTQ community as well, that they will set that part of their identity aside?

- Is there any part of your own personal identity that you would set aside in order to be part of a movement to advocate for a people group you identify with?

- Why should any black person who is working for positive change in this country feel that they must focus only on one part of their identity and not its whole?

- Is a gay black person any less black than a straight one?

- If one black life matters, don’t they all?

Even though this work is hard and at times may feel brutal, it’s necessary and right that we undertake it together. Come back next week, and we will continue to work toward peace, one piece at a time.