This post is part of a year-long series. If my work is helpful for you, consider a contribution through Venmo to support this crucial work of unlearning racial bias.

Whew. Y’all. It has been a week: elections and grand jurors, and Supreme Court appointment and violent death and of course ‘rona is still in these streets.

It’s no wonder I’ve been tired.

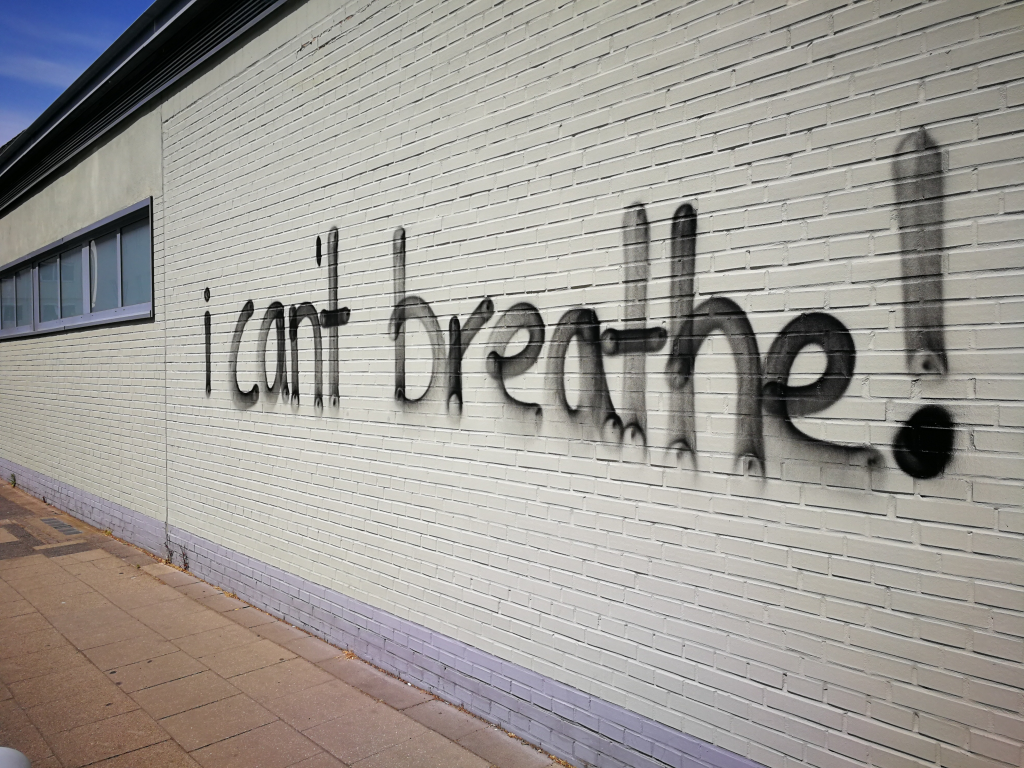

Each time a new name comes across my news feed because a black person has been killed by people who have been hired to “protect and serve,” my body and heart return to an all too familiar weariness reserved for this unique blend of personal and corporate grief. The grief passed down through generations and shared across the diaspora. The grief that fervently hopes blackness won’t be blamed for the death of us all.

There is a heaviness too. How, after all, can one keep track of all the names of people across the country whose lives have been senselessly and violently cut short? Whether they are armed or not armed, waking or sleeping, sitting in a car during a traffic stop or fleeing from fear, the result too often is that a life is snuffed out. Not lost, as is so often the idiom, because we know these lives didn’t forget their way home but will eventually arrive. Rather, these lives are stolen, robbed from their mothers and cousins and friends and spouses – all of their loved ones left to wonder about the life that might have been had it been allowed to continue.

I have noticed that some people refer to these shooting victims by their first names. Casually, as if they were on a first name basis with them while they lived – even though in truth they were not. At first, when I would hear well-meaning strangers speak of these people by their first names, or see them write on social media about them this way, I felt bothered but stayed silent because I couldn’t figure out why my breath held, my pulse quickened.

But then it hit me.

As much as the purpose in using victims’ first names is likely an attempt to humanize them, to make them feel familiar and real, there’s a thin line I think between humanizing these now-martyrs and forgetting just how personal the loss is for their loved ones. It’s right and appropriate for each of us to feel connected to these people and their families. And it’s equally important to force ourselves to sit still in our grief long enough to remember their loved ones’ grief is so much deeper.

When I see my child wear a red hoodie, I see Trayvon Martin’s face. But I don’t hear his voice calling me Cupcake, because I am not his mother.

When I see Mike Brown’s high school graduation photo, I remember lie-ins with protesters laying down on the ground in public, some with signs saying “hands up, don’t shoot.” But I don’t picture him walking to school past a graveyard every day, because I wasn’t one of his classmates.

When I hear Philando Castille’s name, I remember the Facebook live video of his bloodstained shirt as the life drained out of him as he fell to the side of the driver’s seat he was still buckled into. But I don’t remember how he paid for lunch when my parents didn’t have money to send to school with me, because I wasn’t one of the kids who came through the line in the cafeteria where he worked.

I am not saying at all that I have an answer for what the perfect balance is between grieving corporately, righteously agitating for justice, and allowing space for families to grieve their loved ones’ passing. I am saying simply that we have to try not to lose sight of individual people in the midst of our indignation on their behalf.

We know Breonna Taylor’s name but not her favorite color or whether she smelled like cotton candy as a newborn.

We must remember this.

While there are certainly many published books written by bereaved families, the only one I have read for myself to date is Lesley McSpadden’s Tell the Truth and Shame the Devil. She details her own life, her mothering of Mike Brown, their families’ struggles and their triumphs, their love, and their loss. Her words challenged me to see her as a complete person, with a whole lived history with her son, not merely a face in the movement for justice.

As you read and think and reflect this week, I hope you will consider these questions:

- How often have you prayed for the families of victims of violent crimes? Have you sought out information from the victims’ families?

- Have you watched and shared violent video footage of their loved one’s death? If so, have you also prayed for them – not just for justice, but for healing, for peace?

- How can you balance humanizing victims with leaving space for the wholeness of their lived experiences?

I’ll be working at this alongside each of you who undertakes it. I’ve got no answers on this one, but I never want to forget the question. Together, let us never forget that each name that becomes a hashtag and rallying cry was first a human life. Come back next week, and we’ll keep asking and answering hard questions, so that we can find peace, one piece at a time.